- Home

- Beth M. Howard

Making Piece Page 10

Making Piece Read online

Page 10

Marcus had written to me almost identical sentiments just one week before he died: “Giving up this dream is what’s hardest for me. We fought hard for this and that probably makes it harder to let go.”

Self-pity? No. Losing a limb and having to learn to live without it? Yes. If only there was a prosthetic for grief.

Pushing the questions—and shameful thoughts—aside, I dug beneath the lard-heavy layers of grief to tap into whatever reserves I had left in order to get to work. In the same way I tackled magazine articles, I would identify who to interview, call them to schedule a visit and then show up to ask the questions. The biggest difference was cameras. And makeup. I was going to need a lot of foundation and concealer—definitely concealer—to hide my puffy, tear-damaged eyes and the stress-induced case of dermatitis, a growing rash that surrounded my eyes and nose with inflamed and ugly red spots.

The first phone call I made for the pie show was to L.A.’s top pie expert: my dad. My parents had moved from Iowa to California when the kids came back for fewer and fewer visits. Three of us had moved to Los Angeles and my parents spent so much time visiting us they finally got their own vacation apartment, which led to selling their house in Iowa, which led to early retirement by the sea. Smart people. They had spent the first two years of their marriage in San Diego, where they gave birth to the first two of five kids and conceived me. As far as I was concerned, my conception in their Ocean Avenue apartment meant I could lay claim to dual origins—part California girl (sunny and free-spirited—I used to be anyway, before Marcus died) and part Native Iowan (hearty and grounded), a fact that I like to publicize because it sums up the definition of me so well.

“You don’t need to tell people that,” my mom scolds.

“Why? Because people will think you actually had sex?” I tease her the way I learned from my dad.

They settled in Iowa, but always longed to move back to the West Coast. And they finally did pull up their Iowa stakes, in 2001, and have lived blissfully at the beach ever since. No sooner had my parents unpacked their moving van in L.A., however, I left my pie-baking job at Mary’s Kitchen and moved to Seattle for a project (one that actually paid), then I married Marcus and moved to Germany, then…well, they couldn’t keep track of me after that. My dad complained about me taking up so many pages in his address book. “You should see all the scratched-out entries I have in there,” he said every time I added a new residence.

But I was in L.A. for the time being. Four months after Marcus dying. Staying at Melissa’s a mere ten miles away. Avoiding them. I needed to do something to prove I wasn’t the World’s Worst Daughter. I didn’t need to add another slasher title to my list, though its rank would have been obvious—it would come right after Bad Wife.

“Dad? It’s Beth,” I had to speak loudly since years of a dental drill whining in his ears had taken a toll. “Can I take you to lunch?”

“Hi, Anne,” he said. “What are you up to?”

“No, it’s BETH. Are you free for lunch? There’s a diner in West L.A. I think you’ll like.” I didn’t tell him I was using him as a cover for my location-scouting trip, as they call it in “the Biz.” He wouldn’t have cared about my ulterior motive, though, because I had a selling point he couldn’t refuse: “They have banana cream pie.”

The Apple Pan is best known for its outstanding apple pie, but their second-most popular pie, banana cream, is even better. Moreover—okay, I’m just going to say it—it’s far better than my mom’s. Especially since my mom had adopted a few shortcuts over the years. First it was just one or two easier steps, but she took it an ingredient too far, entering that dangerous territory my grandmothers had landed in, and eventually arrived at the point-of-no-return. Her made-from-scratch banana cream pie had morphed into one of store-bought graham cracker crust, packaged pudding mix (worse, instant pudding), and—oh, the horror—Cool Whip topping. The only thing that hadn’t changed was the bananas. But even that part had been altered as my mom put bananas in only half the pie because she couldn’t eat them. Didn’t matter. My dad still loved her pie. And he still loved her.

The Hispanic man behind the counter placed two burgers on the counter in front of my dad and me. Just like the old days at the Canteen, they were wrapped in wax paper. The Apple Pan’s staff was made up of dark-haired men in white paper hats and not, like at the Canteen, grey-haired ladies in hairnets. We weren’t in Iowa anymore. Gender and race aside, what was remarkable about both places was the longevity of employment. Ask anyone on The Apple Pan’s staff how long they’ve worked there and you will not get an answer less than, “Thirteen years.” The longest stint was held by a man who retired a year earlier; he worked there fifty-three years. God forbid they hire me. I would ruin their track record. Ditto for the Canteen, where fifteen to twenty years was the average employment duration. Wow. What were these diners doing right? They couldn’t have been paying huge salaries. My deduction—verified by the empty plates on the counter—was the pie. It had to be the pie. And we were about to be served ours. Two heaping slices of banana cream bliss.

Pie was a connection for my dad and me, but pie didn’t inspire the deep and meaningful, philosophical conversations that were possible with him. Our most revealing talks were usually assisted by a three-olive martini or two—and hearing aids.

Our eyes lit up as the waiter set the pie down in front of us. We lifted our forks in unison, diving into our individual slices, cutting through our layers of whipped cream, thin blankets of vanilla pudding and down into the most generous stack of sliced bananas I had ever seen in a pie. Our forks cut through the delicate flour and butter crust until there was nothing left to stop them but the plate.

We ate in silence—with the exception of the familiar, telltale moans expressing our utter satisfaction with the dessert. We didn’t need to talk. There wasn’t anything to say. It was enough that I was there with my dad. Eating his favorite pie. He was still alive and I was grateful for that.

He may not have been able to talk about Marcus, but forgiveness came more easily when I reminded myself that he was grieving Marcus, too. My dad had visited Marcus and me in Germany twice in the two and a half years I lived there, and both times we took week-long motorcycle trips, one time crossing the Alps to Italy and the other to the Alsatian wine country of France. Marcus and my dad bonded over their love for these two-wheeled adventures, but I’m convinced they would have had the same friendship and respect for one another even if they hadn’t had me or even the motorcycles as the common link. What stood out most is how, during my heart-to-heart talks with my dad over martinis, when I confided in him how much I was struggling in the marriage, he would always say, “I like Marcus; he’s a good man.” And then he always added, “You two have something special. I know you will be okay.” But we weren’t okay. And now Marcus was gone. And now, with or without the assistance of a lip-loosening martini, my dad and I didn’t know what to say to each other anymore.

Regardless of our inability to talk, I didn’t take my dad for granted. I couldn’t. He could be gone any second. Anyone could.

When we finished, I paid the bill. That was a change from our childhood Canteen outings, but one thing had stayed the same. When we stepped outside into the warm sunshine, I didn’t have to remind myself. It came out, like a reflex, and I genuinely meant it. I said, “Thank you, Dad.”

CHAPTER

9

With The Apple Pan securing the Number One position on my Must See TV pie production schedule, I continued making phone calls and doing Internet searches until I had filled the rest of the two-week shoot with other pie-related appointments. It was a week before Christmas and all I could do now was wait for Janice’s return to L.A. in mid-January. That, and get through the holidays.

I needed to answer the question that had been looming for weeks: “How would I survive my first Christmas and New Year’s Eve without Marcus?” Many friends worried about me, calling and emailing to offer their good wishes and support. My gr

ief counselor worried about me. I worried about me, too. But I had discovered something important during my drive from Portland to Los Angeles in The Beast: I felt best when I was in motion.

“Perpetual Motion” is the name of the second song I learned to play on the cello using the Suzuki Method. Perpetual motion is the physics theory stating that motion would go on indefinitely if not for the presence of friction. Perpetual motion, and my need for it, is why I left Melissa’s after several weeks there and kept on driving—four hundred miles east to Phoenix, Arizona. I hadn’t planned on traveling to America’s fifth largest city for Christmas, but Alison had invited me to join her and Thomas at her mother’s condo in the suburb of Scottsdale.

After barely surviving my first Thanksgiving without Marcus, I had a valid reason to be worried about Christmas and New Year’s. And even more reason to seek refuge in Alison’s soothing company.

As a pie baker, Thanksgiving was my most revered holiday. Forget the turkey, stuffing and cranberry sauce, the feast’s sacrosanct dish was pie—pumpkin and pecan. Thanksgiving was also sacred, as it was the one holiday Marcus and I had never spent apart. Through all the job transfers, moves and other upheavals in our relationship there was one, and only one, consistent thing: Thanksgiving. We had celebrated the past seven Thanksgivings together—two in America with my parents, two in Germany with his parents, one in Switzerland with my friends in Bern, one in Mexico with his boss and other American coworkers and one on board a Lufthansa flight somewhere over the Atlantic the year Marcus’s grandma died.

Three months after my return trip from Marcus’s funeral on that same German airline, I didn’t feel much like celebrating Thanksgiving, let alone making pie or even eating it. But Alison, ever-present, ever ready to cheer me up with her laugh, insisted I join her at the gathering of twelve in her home.

“And would you be able to bring the pies?”

“Yes, yes, of course, you can count on me.” I was glad for the assignment.

The Spurs Award. You fall off your horse, you run after it, chase it down, get back on and ride again. If pie baking was my new proverbial horse, my mixing bowls were my saddle; my rolling pin, my reins; my apron, my cowboy boots.

With the late November rain lightly tapping on the skylights in my tiny studio apartment kitchen, I turned up the volume on my iPod to fill my ears with the Bach cello music from our wedding and drown out my thoughts. With my hands moving to the rhythm of the string instruments, I rubbed the butter and shortening into the flour. The soft white powder and tender yellow and white fats melded together between my thumbs and forefingers. I never tired of the process; I loved watching textures combine to create a new, even softer one.

Alison refused to make pie dough with her hands. She made ongoing jokes about her love affair with her food processor. But to me, it wasn’t funny. Making pie dough was all about the senses, the tactile experience, the sensory messages sent from the fingertips to the brain signaling the right consistency had been achieved. Only with your bare hands could you be sure the dough had enough moisture, and have the confidence, the intuitive knowing, the connection with your food. Only by touching the dough, having direct contact with it, could you imagine yourself as a sculptor, or awaken your inner child, the one who loved making creations with Play-Doh. You just couldn’t reach that sensual depth with a Cuisinart.

I filled four crimped crusts, two with the liquid pumpkin-spice mixture and two with the viscous pecan concoction and placed them in my oven that was so small the pie rims touched. My precious babies baked and browned; their sweet scents permeated my tree house and evoked a sense of pride. Hooray for me. I had done something productive, gratifying—making pie for friends, people I loved, people who loved me. I was relieved to discover I still possessed a bit of my “old normal.”

A friend who had witnessed my transition from dot com producer to pie baker at Mary’s Kitchen had commented back then, “Beth, you’re happiest when you’re making pie.”

He was right. Though I couldn’t yet say I was “happy,” making these pies, my first since those hot August days in the Texas miner’s cabin, had reminded me I could still get that peaceful, easy feeling. Hell, I hadn’t even cried all day. For a fresh widow going through her first major holiday alone? Damn, I was doing great. Bring on the gold star for the grief student.

I dropped off the pies at Alison’s that night, on Thanksgiving Eve. I must have had a premonition that I might not make it to her dinner party.

By five o’clock on Thanksgiving Day, I was dressed and ready to face the holiday, flying solo. I had put on nice jeans, a paisley blouse and, as a nod to Marcus, my Bavarian Trachten wool blazer. He would have liked that. I had spritzed myself with perfume and applied the final strokes of mascara. I grabbed my car key off the hook by the door and then… Oh, I should have seen it coming, should have known it was going to happen, should have been prepared. I felt a sudden stabbing in my heart. Tears shot out from my eye ducts without warning. My mouth dropped open to release a silent scream. My knees buckled and I slumped down on the floor, my forehead pressing into the wood, rolling back and forth the way it had done on the concrete in Texas the night Marcus died. The tears raced out so fast and forcefully I thought I might vomit. Forget the turkey, some kind of electric carving knife had found its way into my chest.

“A grief burst,” Susan explained later. “That’s what you had. It’s the sudden and overwhelming onset of grief. They can happen anytime and they come without warning.”

My grief burst and its crippling onslaught of despair caused me to miss the appetizer and cocktail portion of the festivities. When Alison and family were ready to sit down for the main meal, wondering why I hadn’t yet arrived, I got a phone call.

“It’s unlike you to be late. Are you okay?” Alison asked.

“I’m sorry. I can’t come,” I told her. “Every time I try to leave the house, I start bawling again.” As it was, I couldn’t talk on the phone without gasping in between sobs.

“I’m coming to pick you up. Don’t worry about packing for the dogs; we have food for them. Just bring your pajamas.” She put the roasted bird back in the oven to keep it warm, drove the twenty minutes across town to my house, and sat with me for another fifteen minutes at my kitchen table to talk me down from the ledge.

“Don’t jump,” she might as well have been saying. “But if you do, I will use my net to catch you.” Patient, loving, kind, even with ten people and a turkey waiting at home—this is why Alison was voted Homecoming Queen, why her number was right next to Nan’s and Melissa’s in my speed dial. And why I would spend the next holiday with her. Christmas. In Arizona.

In spite of parking the RV upon arrival in Scottsdale, I stayed constantly in motion—hiking every morning in the local mountains, swimming every afternoon in the condo’s pool, cooking big meals and making pie, a blueberry crumble, since we bought a bulk-size carton of blueberries from Costco.

Also during my week with her, Alison got me to do something I’ve never done: color my hair. Alison’s sister Emily helped pick out a boxed blond shade from the grocery store and the two sisters played the roles of both beautician and therapist and lightened me up. Really, I did feel lighter. Not just because of my new hair color, but because I had made it through Christmas without having a complete Oh-My-God-I-Can’t-Believe-Marcus-Is-Dead Meltdown. Too bad they couldn’t do anything to fix my puffy eyes. When Alison and Thomas’s vacation time ended, I couldn’t bring myself to leave the desert and its brilliant, blazing sun. If staying in motion was helpful, being in the sun was doubly so. Seeing as I was unemployed, lost, confused and still mired in grief—and didn’t have to be back in L.A. to meet Janice for another few weeks—I simply drove The Beast twenty-some miles down the road to my aunt and uncle’s home in Mesa.

Uncle Mike and Aunt Sue were snowbirds from the Midwest, meaning they retired early and spent their winters golfing in Arizona rather than shoveling snow in Iowa. They lived in a trailer park for people

age fifty-five and over, and though I didn’t qualify in the age category I was nonetheless welcomed as a guest. The RV fit right in to the scene, parked among the double-wides, and we settled into a busy schedule that included more hiking, swimming, hot-tubbing and watching movies from the horizontal comfort of La-Z-Boy recliners. Escaping into films like The Secret Life of Bees engaged my heart and mind enough to help me forget.

Lest I get too comfortable in retirement mode—and I could have easily seen myself getting accustomed to the recreation-packed lifestyle—I packed up the dogs and drove out of the trailer park. Unsure of where I was going next—maybe back to L.A., maybe find a campground outside Phoenix, maybe head north to Sedona—I was stocking up on supplies at a local Trader Joe’s when my cell phone rang. It was Maggie. Maggie was a friend from Chicago (who I met in passing at a hotel in Nairobi, Kenya—but that’s another story), whose husband, Paul, had died of a ruptured aorta six months before Marcus.

“I’m in Phoenix, staying with my friend Christina,” she said. “Come join us for lunch.” So I drove the RV only ten miles west, to downtown Phoenix, parked the RV under the trees of Christina’s old town hacienda-style home and went out for lunch.

Lunch lasted two and a half days. Christina was also a widow. Her husband and Maggie’s husband were best friends. We recognized the irony of being “Three Merry Widows” and thus glommed together like undercooked pie dough. “If you don’t have to be anywhere for New Year’s Eve,” Christina said, “then stay here with us.”

How else would I have gotten through the hype of this dreaded holiday? Instead of being forced to fake that we were happy about welcoming a new year—a year that would be void of the men we loved—we got busy in the kitchen. Christina grilled steaks (Marcus would have loved that), Maggie made the salad and, naturally, I baked a pie—apple.

As the minutes ticked past 11:59 p.m. to 12:00 a.m. to 12:01 a.m., I breathed a sigh of relief that, officially, the holidays were almost over.

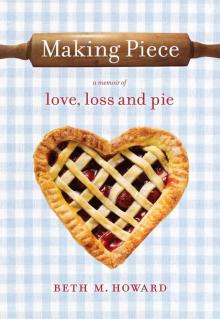

Making Piece

Making Piece