- Home

- Beth M. Howard

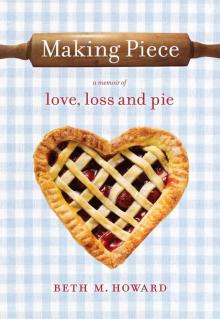

Making Piece Page 13

Making Piece Read online

Page 13

The mystique Dorothy created around her crust may have been a gimmick—as opposed to anything illegal—but we would never know. If it was merely a marketing ploy, it was working so well that even inmates on death row were requesting a slice of Mommie Helen’s pie for their last meal.

Dorothy packed up a couple of wedges of sweet potato and pecan pie for Janice and me to take with us. The second we dropped the camera gear in the RV, we dug in with our plastic forks. Indeed the Southern-style dessert was outstanding. Worthy of waiting in a line with six hundred people or ordering as a last meal? That I couldn’t say. But it didn’t stop me from devouring a slice of the sweet potato’s nutmeg-laced custard without stopping to swallow in between bites.

Our road trip may have been loosely structured, but it was tightly scheduled. We debated postponing our next stop due to bad weather. We were heading to Oak Glen (elevation 2,800), Southern California’s apple-growing region eighty miles east of Los Angeles, and only an hour’s drive farther east from Mommie Helen’s sweet potato pie palace, but if we postponed, we would have had no chance of coming back.

It had snowed in Oak Glen the previous day. If you were a skier, you would be happy about that; if you were driving a twenty-four-foot RV, you would not. I had become more and more comfortable driving The Beast, but I wasn’t going to knowingly put myself in harm’s way—even though I bought snow chains before leaving Portland. Alas, after much discussion and constant checking with the weather service, we motored up the mountain, climbing higher and higher in the rain. There were no signs of snow—only safety billboards flashing warnings of mud slides—and we arrived safely in the orchard-filled mountain town.

There may be no better way to spend a cold, miserable, wet day than to sit inside a wood-heated mountain diner in a cozy booth talking about—and eating—pie. Cinnamon-sauce apple pie à la mode. With endless cups of coffee. No offense to Susan in Portland, but this might have been more effective than grief counseling.

We were at Law’s Oak Glen Coffee Shop, meeting with three generations of pie bakers and apple growers. Sitting across from me in the booth was Theresa Law, the matriarch of the family. At age ninety-two, impeccably dressed in her pale blue sweater and tweed scarf, her hair dyed blond and expertly curled, she was still clearly in charge. Her daughter Alison, who looked to be about sixty, sat next to her, trying to finish Theresa’s sentences, but her mother ignored her and kept on talking. She was telling us about the history of Oak Glen.

“The Mormons settled the area in the 1800s and planted the first apple orchards here,” the matriarch said. “I lost my first husband in World War II. I got remarried and drove cross-country in the 1940s, from Maine all the way to Oak Glen, with my second husband. I first baked pies in my wood-burning stove in my home. When we opened the diner, we sold out of pies the very first day.”

“Her baking record is 657 pies in one day,” Alison touted.

“How is that possible?” I asked. “My record is two hundred in one day, but that included an all-nighter on top of one week of prep. And I was left with swollen hands, sore muscles and burned arms.”

“We had help,” Theresa admitted. “But you should have seen the customers. They just kept showing up at the take-out window.”

The waitress poured more coffee and said, “Kent is ready for you to come into the kitchen to film him making pie.” Kent was Theresa’s son, who ran the restaurant.

I followed the waitress and Janice and the camera to the kitchen, just behind the diner’s counter. Kent, Alison’s gray-bearded brother who looked more like a construction foreman than a baker, showed us his pie-making equipment. His work space was about as big as a sailboat galley. “You put the dough in here,” he said, as he fed a softball-size hunk of his flour-and-shortening mixture into a heavy-duty mechanical roller called a sheeter. In a split second, the machine spit out the dough on the other side, flattened like a piece of printer paper, round and ready for the pie plate.

“I could make 657 pies in a day, too, if I had one of these,” I remarked to Janice.

“I’m making ten today,” Kent said, unaware of my sarcasm.

I had mixed feelings about all the mechanical aids. I believed that pie should be not just homemade but handmade. To use a machine meant losing the physical, visceral and, yes, spiritual connection to your creation. We live in a world where we are already so disconnected from our food and where it comes from, that when it came to pie, I found myself clinging to the old ways, the lower tech the better. Even though it couldn’t be proven, I liked to think people who ate the handmade pies could taste the difference from the machine-made ones, that they could feel the love and the human touch that went into making it.

Technology-assisted or not, clearly Kent was passionate about his pies.

We hung around (and taped him) as he assembled the pies, piling in sliced apples and sugar. He was moving around with such an air of happiness, he was practically whistling. It struck me as an interesting role reversal that he was so at home in the kitchen, while his sister had found her niche running the family produce stand across the street.

We rejoined Theresa and Alison, who were still sitting in the booth working on their tenth cup of coffee. Alison talked about her battle with cancer. “Apples cured me,” she insisted. “You know that expression, ‘An apple a day?’ The pectin in the apple removes toxins from your body, but you have to eat the peel. I started eating apples every day and the cancer was gone.”

I was about to make some quip about how I wished apples could also cure grief, but luckily I was interrupted by apple pie. Kent arrived at the table, holding one of his finished pies, now crusty and steaming and wafting its seductive scent under our noses. He presented it to his mother for inspection and Theresa examined it thoroughly, as if the pie had to pass her quality-control check. She peered closer, her eyebrows pulled together, her eyes focused on the pool of filling that had bubbled up on one side. The top was evenly browned, the crust edges were intact. (Kent didn’t make a fluted rim; his was flat and uncrimped.) Janice turned her camera on the pie, and managed to get Theresa on tape, finally giving the pie her approval. She was a tough old boss. Mary had never scrutinized my pies like this, in spite of our demanding Malibu customers.

The moment we had been anticipating for four hours had finally arrived. We were served the pie. Drowning in a pool of Kent’s special caramel sauce and buried under two huge scoops of vanilla ice cream, there was a slice of pie on the plate somewhere. With soup spoons, Janice and I shoveled bite after bite into our mouths, faster and faster in a race against the melting ice cream, until we were so stuffed we moaned with pain instead of pleasure.

After our pie-eating orgy, Alison took us over to her fruit stand, Mom’s Country Orchards, for a tour. Surrounded by fields of bare fruit trees, the single-story wooden building was painted brown with green trim and decorated with sunflowers and hand-painted placards advertising the availability of honey, cider and, naturally, apples. In contrast to the warmth of the restaurant, we fought the chill of the cold rain we picked up in the empty parking lot until long after we were inside the produce stand. Alison introduced us to her son, Jake. “He’s the third generation in our family of apple growers,” she said, patting him on the shoulder of his Carhartt jacket.

“Nice to meet you,” said the husky, blond-bearded guy, who then went back to what he had been doing before we arrived, stacking crates of apples on the concrete floor.

Alison proceeded to explain the many varieties of (cancer-curing) apples they grow and sell up in Oak Glen. I normally use Granny Smith in my pies, occasionally supplementing these with Royal Gala or Braeburn. But Alison, expanding our pie horizons, showed us apples we’d never heard of like Black Twig, Bellflower, Arkansas Black, and too many others to remember without the help of her wall chart. I was shivering too much to care at this point. Plus, I was uncomfortably full from Kent’s pie. I wanted to go back inside the RV, turn on the heater and take a nap in my down nest in the ba

ck.

Before wrapping up the final Law family interview, we had one last objective: buy apples. We needed more apples than we could get at a grocery store because I was going to make fifty pies the next day. It would have been easier to just buy the pies from Kent, but making them by hand was too important. For many reasons.

Alison called out orders to Jake, who disappeared out the side door of the produce stand. He turned up a few minutes later with five cases of apples loaded on his dolly and rolled them out to the RV. As The Beast was already full of my gear, Janice’s luggage and Team Terrier’s supplies, we were tight on space. We found room for the nearly two hundred pounds of apples by stacking the crates in the shower stall, where some of my clothes were hanging on the inside of the door. Those clothes would smell like apples for weeks afterward. And Janice, who slept next to the shower on the RV’s kitchen banquette-turned-bed, would report later that one of her most prominent memories about the shoot was not the people or the pie she ate, but breathing in the scent of these apples as she slept.

“Hey, Janice,” I said as we wound our way back down the mountain, leaving the quiet orchards behind and reentering L.A.’s congested freeway chaos. “How would you feel about stopping in Koreatown on the way back to Santa Monica?” I was cold from our last few days of shooting in the rain, and tired from trying to maintain my on-camera presence, while really just wanting to go lie down and read my newest grief book, so perfectly titled I’m Grieving As Fast As I Can. I knew a place I could go to get warm and rested: Natura Spa. “We’re going right past the spa on our way back to Melissa’s.”

“Sure, sounds awesome,” she answered in her best Jersey Girl accent as “sure” sounded more like “shu-wah.” Even when she wasn’t trying to be funny, her voice alone humored me. Not only did I love the way she talked—or, as she would say, “twahked”—her always-light and effervescent mood made her such good company. We had become a tight-knit team of two. Four, if you counted the dogs. But Team Terrier had been left behind at Melissa’s for this part of the shoot.

I handed her my BlackBerry to look up the number and schedule appointments for the ninety-minute body-scrub-massage combo. “I think we can make it there by five.” I was suddenly very alert and energized. I couldn’t wait to get out of the RV—and out of my clothes.

I had been to Natura Spa once. I went with Melissa when I stopped in L.A. en route from Terlingua, moving back to Portland. It was early October, only a month and a half after The Day That Changed My Life. Melissa had just learned about this spa from her magazine publisher friend, Trish, who had become a Natura devotee. While Melissa could have gone anytime she wanted, it wasn’t until I showed up on her doorstep in my discombobulated, depleted condition, like an earthquake still having aftershocks, that the time seemed right. She whisked me off immediately to Koreatown.

There—in the basement of a department store on Wilshire Boulevard, in a tile-walled shower room, lying naked on a vinyl-covered table surrounded by other naked women lying on tables next to me—is where I found God.

God was a chubby Korean woman dressed in a black lace bra and panties, and she was inflicting a new kind of torture on me. Instead of the emotional pain I was used to, this was purely physical. Her loofah sponge or scrub brush—or steel wool or wire brush or Brillo pad or whatever torture device she was using—bore so deep into my skin I thought I might be bleeding. And yet, I didn’t resist. I let her continue roughing me up, my senses awakened and invigorated as her brush invaded the deepest reaches of my body, scratching places only Marcus had ever touched. Her brush ventured under my armpits, across my breasts, in circular motions on my belly, into my groin and, when she rolled me over like a filet of beef, her brush found its way into the hidden recesses behind my ears and even into my butt crack.

This kind of treatment was not for prudish types. Melissa was squeamish about the flesh-factory atmosphere at first, but I wasn’t. I had been conditioned to public nudity in Germany after many visits with Marcus to the coed naked mineral bathhouses, where I had gladly shed my modesty along with my bathing suit in order to soak in the effervescent hot spring pools—my favorite being the Kristall-Therme in Schwangau, in the shadow of King Ludwig’s Neuschwanstein Castle. Natura was women-only, mostly Koreans who were going about their own beauty rituals and unconcerned with our white-girl presence, naked or not. We were simply paying and willing victims of the brush.

Lying on my stomach with my head turned to the side, I opened my eye just long enough to compute that the chunks of gummed up eraser covering the previously clean table were actually pieces of the skin that used to cover my body. I knew what it was like to get a sunburn, when afterward I could pull my skin off in sheets—much like the way I peeled an apple. But I had never lost an entire epidermal layer from a spa treatment.

The underwear-clad therapist doused me in a bucket of warm water, rinsing the blackish-grey debris off my body onto the floor and down the drain. She didn’t know it—and she couldn’t have cared less, judging by the sounds of her noisy Korean chatter with her coworkers—but the skin she had removed was much more than a bunch of dead cells; she had relieved me of a whole layer of death-related grief.

With my new substratum exposed, the Korean woman’s touch—or at least the stiff fibers of her sponge—had put me back inside my body. It was as if my soul had been detached, not inhabiting the vessel it was born to, yet I wasn’t fully aware of how disconnected I was until this overweight, torture-device-wielding sadist aggravated my nerve endings to the point of waking me up.

But the biggest payoff was not the baby-smooth texture she had given my skin. Nor was it the reduced eye puffiness from the cucumber mask she had slathered on my face. It was something much more important. Eight weeks after my husband died, feeling like I had died with him, I was lying on a table, getting worked over and hosed off by a woman who might as well have been a wrestler. While my naked body was at her mercy, I was struck with an important revelation: I am going to be okay. Maybe not right away, but I was aware that I was indeed still alive and that I was capable of feeling something other than numbness.

Dorothy Rose Pryor of Mommie Helen’s Pies had Jesus and her Baptist revivals to feed her faith. Alison Law had cancer-curing apples as her personal miracle. I had my own God, my own restoration of spirit, my own place of worship. And I was about to introduce Janice to it—to baptize her in the mugwort-infused waters of the Jacuzzi, the eucalyptus vapors of the steam room and the spiky scrub brushes of the women in black bras and panties. Pie could wait. We were headed to the spa in Koreatown.

CHAPTER

12

Every year on January 23, America celebrates National Pie Day. The date was officially registered in Chase’s Calendar of Events by a man named Charlie Papazian, a Boulder, Colorado-based schoolteacher who happened to love pie and thought there should be a day to commemorate his favorite dessert. January 23 was his birthday, but this guy would have nothing to do with frosting and sugary decorations.

“Cake, be damned. I only want birthday pie,” he proclaimed.

He was so serious he registered his date of birth as Pie Day. This led him to create an entire organization, which he called the American Pie Council. At first the APC held homespun pie contests in the shadows of the Rocky Mountains’ Front Range. Soon, the big, commercial pie makers wanted to get in on the action. They wanted to win the blue ribbons. Since the machine-made versus handmade competition was unbalanced (and the commercial pies couldn’t win), they lobbied to create their own category. After much arguing, posturing and finger pointing, the grassroots bakers and the muscle-bound frozen-food brands just couldn’t reconcile their different approaches to pie. The corporate muckety-mucks didn’t think the APC founders were thinking big enough. They wanted to expand beyond the quaint pie contests and picnics in the park, so they took over the organization, moved it to Chicago, and now the American Pie Council shares office space with a pie-assembly-line manufacturer. That’s one side of the story an

yway, the one you won’t find on the APC website.

All I knew at the time was that January 23 coincided with our pie shoot, and we wanted to—had to—include National Pie Day in some way. How we would do it, Janice and I had decided, was to assemble my closest friends, the ones who were helping me with my Grief Survival Training and, together, the day before, bake fifty apple pies—pies that on the actual holiday would be handed out by the slice on the streets of L.A.

I called them Team Marcus, but in a show of their alliance to me, they insisted on calling themselves Team Beth. Whatever. The team included Jane, my British baker friend from Mary’s Kitchen, who now ran a high-tea catering business; Nan, who I had just seen in Phoenix and was now in Hollywood producing and starring in a play she wrote; and Melissa. Melissa’s mom Carlene was there, too, visiting from Maine. And Thelma, Melissa’s full-time Guatemalan housekeeper, offered a hand.

Melissa arranged with her estranged husband to use the kitchen in their old house, where he still lived, two blocks from her new smaller-but-much-cuter house with the swimming pool. Her Viking range would have sufficed, but the ex had a double oven, and quadruple the counter space.

“But you have to be gone by five,” he said. Five was an arbitrary time. There was no reason we would have had to leave by then. He just wanted to set conditions, to prove he was still in control. I would have been fine just baking at Melissa’s. We could have made do with her smaller kitchen. But with six bakers and one cameraperson, the extra space was appreciated. (I would thank him later by giving him a pie, to which he would reply, “I don’t like apple.”)

Making Piece

Making Piece