- Home

- Beth M. Howard

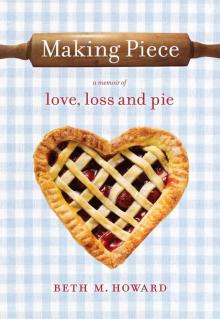

Making Piece Page 7

Making Piece Read online

Page 7

Portland may be renowned for its food scene—its socially conscious cafés supplied with locally grown produce and free-range, hormone-absent meat, its proliferating gourmet food carts and its frequent glowing reviews in the New York Times—but at the time, Portland did not have any pie shops. Still, it had decent pie. Not mind-blowing-delicious pie, but there was pie all the same. And pie is what I needed. Like a gardener savors digging their bare hands in the earth, drawing energy from holding a clump of root-bound soil between their palms, I needed pie dough. I needed to bury my hands in flour and butter to evoke that grounding, energizing sensation. I made a list of the places where I would apply: Crema, Random Order Coffee House, Bipartisan Café, Grand Central Bakery, Baker and Spice. Out of five places, I was sure to get a job. After all, I was highly qualified.

At least by my definition I was qualified. Granted, it had been eight years since I worked at Mary’s Kitchen. But I had spent a full year there making pies, and my on-the-job training had to be as valuable as a culinary school certificate.

If my pies passed the test from Hollywood’s A-list celebrities, I was certain my pies would hold up to Portland’s precious culinary standards.

First, I applied at Crema, a hip little bakery in Portland’s northeast quadrant. I was attracted to the contrast of wholesome, hearty baked goods—scones, muffins, cupcakes and pie—sold in an ultramodern glass-front building with concrete floors. It’s what Marcus would call a “style-mix.” In truth, I went to Crema first because it’s a place Marcus and I liked. He had taken Alison there for a thank-you breakfast just days before he died. She told me about it later, about their conversation, about how sad he was over our divorce. I still had the receipt from their breakfast, which I found in his wallet, along with the other sales slips that tracked the movements of his final days. Even when I was not conscious of it, everything I did, everywhere I went now, was motivated by staying connected to Marcus.

I approached the twentysomething dude with the plug-pierced ears and scraggly beard behind the cash register. “Oh, man, sorry, we’re not hiring,” he said. “But you can leave your number.”

I didn’t scribble my number on the scrap of paper he offered. I left my card. I had come a long way since my baking days in Malibu. I took pie so seriously now I had a business card printed with “The World Needs More Pie” as my company name, complete with a red-and-white-checkered border and a steaming pie logo on it. Crema’s manager was sure to call me back. Not only was I professional in my approach, I was perfect for this place. The kitchen behind the bakery counter was calling to me. I was already visualizing myself pulling my gorgeous pies out of their ovens, joking and laughing with the other bakers, making friends with the pie-consuming customers, maybe even getting this cashier dude to help me peel apples. This was a place where I could relive the good old days of Malibu. They had to call me back.

Next, I went to Random Order Coffee House about a mile farther northeast. In the heart of the Alberta Street district, Portland’s grunge strip, the predominant feature of this tiny coffeehouse was its display case of handmade pies. Not cheap by any city’s standards, their pies sold for twenty-eight bucks each. Pretending I was looking for the restroom, I poked my head into their baking kitchen in the back. It wasn’t a kitchen exactly, it was more like a closet. A very, very small closet. They were baking all those pies in a bloody toaster oven. No, we weren’t in Malibu anymore. I inquired anyway. No. Not hiring. Whatever. I left my card.

Bipartisan Café is a longer trek east, as far opposite of my Grieving Sanctuary as you could get and still be in Portland. But their pie was as good, plain and simple as a grandmother—er, in my case, great-grandmother—would make. Their specialty was Northwest berry pies—marionberry, blackberry and raspberry—all served with a giant dollop of whipped cream. From what I could tell, the pies were baked right behind the counter, a space already congested with coffee machines and their harried staff members preparing soup and sandwiches. I stayed to eat a bowl of chili—one that actually had meat in it (surprising for vegetarian-centric Portland)—and after some subtle questioning of the waitress, I learned that they might be hiring extra help for Thanksgiving. Unfortunately, the baker was out of town for two weeks. I left my card.

After that, it was on to Grand Central Bakery. This was the biggest of the bunch. Grand Central Bakery was a chain started in Seattle, and had recently released an impressive new cookbook. Their wholegrain breads were sold in grocery stores, and they had started a new line of frozen pie crust and unbaked frozen pies. A burgeoning pie enterprise? They could use my help. Of their three Portland locations, the one closest to my house had a public viewing area to watch the bakers make bread in a warehouse-size kitchen. I watched. I liked. The bakers worked as a team, as one completed their task they passed the bread dough on to their coworker for another task, chatting and smiling all the while. I wanted to join in the camaraderie. I was even willing to change camps and make bread instead of pie. If they were hiring. My neighbor, Robin, worked there part-time as counter help. Even with her hand-delivering my application and putting in a good word for me, I never got a call back.

Baker and Spice, out in the suburbs, was my last resort. When I thought of getting a pie-baking job to help heal my grief, I had envisioned riding my bike to work, like I did in California. Those were heavenly days when I could pedal the forty-five minutes from Venice to Malibu along the warm and sunny coast, watching pelicans dive for fish and surfers catch waves.

Heaven did not exist in Portland, where rain clouds dumped their moisture 24/7. Riding my bike in the rain was one thing. Riding my bike in the rain to the suburbs was another. It didn’t matter. They didn’t want to hire me anyway. The girl in the ratty braids and T-shirt too small for her chubby figure made it clear I wasn’t welcome.

“We. Are. Not. Hiring,” she spelled out in her snotty-pants tone. She wanted me to know I wasn’t one of them.

But what was “them?” I could not figure it out. What was I doing wrong? Maybe Portland bakeries thought my background as pie-baker-to-the-stars was too glitzy and glamorous for their granola-crunching taste. If I was twenty years younger and had Portland’s prerequisite facial piercings and arm-length tattoos, would I have qualified? Or could they see straight through my forced, fake smile and into the sadness behind my tear-swollen eyes?

I started to get mad at Marcus. Is this how you’re punishing me? You’ve turned me into a hideous, repulsive hag. My eyes are so red and puff y, my grief so palpable and heavy, my depression so obvious, no one wants me near them. I was in such bad shape I couldn’t even get a part-time, minimum-wage-paying, pie-baking job. I used to make six figures a year and now I was an unemployable grieving widow. How far and fast we can fall. Fine. I deserved it.

I tried not to be mad at Marcus. To make peace with him, and with myself, I wrote him letters almost daily. I wrote in a notebook that had started off as my journal, but from August 20—the day after his death, during my flight from El Paso to Portland—I wrote him letters in it. I haven’t stopped writing since. I’m on my fourth notebook, all letters to Marcus, explaining how I would do things differently—not complain as much, have more sex, cook without copping an attitude, stick it out instead of running away, be a better wife. I wrote and wrote and wrote—still write—and asked him for forgiveness.

I also wrote in my letters that I needed him to do things differently: come home earlier from work, watch less television, be more romantic, give me more compliments (easier said than done for a German!), take me out for dinner on my birthday. I don’t need a birthday present, my love, but would a card be too much to ask? Talk about our issues instead of staying silent and stoic, don’t be late, don’t keep me waiting.

Everything was written in an apologetic and loving tone. Mostly. There were the days when all I wrote was WHY DID YOU DIE? WHY DID YOU DIE? WHY DID YOU DIE? And other days, when I wrote I MISS YOU. I MISS YOU. I MISS YOU.

I continue to fill entire pages of my note

book with these words. And yes, in all caps. I am repetitive in my requests, my pleas, my apologies, but since he can’t reply, I can never get the resolution, the consolation, the closure I need. And so I keep writing, repeating myself, hoping I might come to my own resolution some distant day, no matter how many notebooks it might take.

The days dragged on. None of the bakeries called me back—even after leaving phone messages and revisiting all of them, dropping off extra cards, just in case.

I kept busy, reading my grief books, adding new titles every day, like, Widow to Widow and The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. I settled into somewhat of a routine—I choke on the words to say I was adjusting to my “new normal.” Normal or not, routine—or any kind of structure—is a useful thing to a grieving person. I had developed a triangular pattern of movement. I went from my house—and my daily long, meditative dog walks on the muddy hiking trails behind it—to Susan’s counseling office across town, where I obediently and eagerly attended my private sessions. From there, I went to Alison and Thomas’s house for movie nights with Alison, when Thomas was working late or out of town. Alison and I would eat popcorn and slice-’n’-bake chocolate chip cookies while watching romantic comedies (basically, movies Thomas would never watch) and tried to stay warm under piles of fleece blankets.

Because our storage unit was too full, Marcus had left his red leather Stressless chair at Alison and Thomas’s. It was Marcus’s European version of the Barcalounger—sleek, minimalist and modern. Its temporary home was the TV room and whenever I came over I was allowed priority seating in it. Even when I would just drop by to say hi, I would secretly take a few minutes to sit in the chair. While Alison was busy in the kitchen or bathroom, I would squeeze the arms, channeling Marcus, pretending I was sitting on his lap, pretending that the chair was him. I pressed my weight into it, hard, to absorb into my skin any hint of his lingering presence.

I had a love-hate relationship with this chair. Marcus bought it when we lived in Portland, and then moved it to Mexico. He spent his weekend days in Mexico lounging in that recliner, dragging it outside onto our sunny terrace where he read, drank lattes and ate toast smeared with Nutella for breakfast and toast piled with sliced avocado for lunch. He would still be in that damn chair in the afternoons, when he switched from coffee to pilsner, and swapped his business books for motorcycle or mountain-biking magazines. I realized he was tired from his work week and needed his rest. The fertile beauty of the pecan farm, the vitamins from the sun on his naked body (Europeans don’t like tan lines) and the quiet contrast from the truck factory construction site, all helped to revitalize him from his stressful job. Still, after being housebound all week—apart from my daily Spanish lessons—I blamed that chair for keeping us from taking weekend road trips to explore our new surroundings.

But, I had to admit, it was a good movie-watching chair. Moreover, it was in this chair, while drinking wine and talking with Alison that I was struck with some brilliant inspiration.

Since no one would hire me to bake pie for them, I would open my own pie shop. Ha! I had talked about the idea for years. Ever since I’d left Mary’s Kitchen. Establishing my own shop would represent what Marcus always thought I was lacking: stability. He had left me a small inheritance. I would use the money to open a pie shop in Portland. I would name the shop after him, or at least offer a rotating pie-of-the-week and call it “The Marcus Special.” I would write the names of his pies on a chalkboard. I would have red-and-white-checkered tablecloths. I would create a cozy place where people would sit with friends to share pie and conversation, and feel so welcome they would linger for hours. I would make Marcus proud.

I told Susan about my idea in our next session. She nodded and smiled and gave me a gold star for the concept.

“Making plans is a good sign,” she said. Any sign that I wasn’t going to slit my wrists or hang myself with Marcus’s bathrobe belt was a good sign to her.

The excitement about the idea lasted approximately one day. All I had to do was sit down at my computer and start an Excel spread sheet listing the expenses it would require, and I was instantly reminded of why I had never opened a pie shop before. I scrapped the idea and went back to bed. But that one day of excitement, fleeting as it was, was better than nothing.

CHAPTER

6

If I thought it was expensive to open a pie shop, I learned that it’s even more expensive to die. I know this because I had to deal with Marcus’s affairs. I had to pay the ambulance bill. And the emergency-room bill. And the emergency-room doctor’s bill. I paid the funeral home for the service and the casket and the courier service to get Marcus’s paperwork from the German consulate. There was the Portland reception, the pizza, the wine and, because Marcus’s friends were mostly Germans, the beer.

In Germany, there was another casket to buy (a fancy wooden one used only for the church service—what became of it afterward, I still wonder), the cremation, the urn for the ashes, the burial plot for the ash-filled urn.

One is not allowed to keep the ashes in Germany, let alone scatter them at will. This is another one of those examples which underscores our cultural differences—countless American fireplace mantels serve as the final resting place for dead relatives, and U.S. mountaintops and oceans are freely, liberally, legally sprinkled with the remains of lost loved ones. I’d settle for a place less grand, with less fanfare, perhaps a small field filled with daisies, preferably in the country. I’d like to think Marcus would rather his ashes be scattered in the juniper heath behind his parents’ house—his favorite hiking spot, located on the northern tip of Germany’s famed Black Forest—but then he was in no position to state his preference. And I was in no position to argue with his German parents, traditions or laws.

I took solace in my belief that it doesn’t matter what happens to our remains. Marcus is not in that urn buried in the ground. He is flying around on a magic carpet, bar hopping at British pubs, making appearances in my dreams, checking in on his coworkers every so often and riding his bike.

A burial serves as a ritual to provide closure; a grave merely serves as a memorial, a shrine. I had no attachment to his grave. The grave was in Germany, a mile and a half from his parents’ house. It was their shrine, not mine. I had made my own shrine in my Portland apartment, covering the top of our Chinese medicine cabinet in framed photos of Marcus, twenty candles at least, and the Happy Buddha statue I had bought him as what turned out to be his last Christmas present. My refrigerator door was covered with pictures of him—Marcus riding a horse on a beach (taken during our honeymoon in Costa Rica), Marcus running on a dirt road through an Italian vineyard, Marcus holding a cup of coffee while sitting on the front porch of a cabin (outside Seattle, where I had lived during our courtship). Anyone who entered my Grieving Sanctuary might have thought my shrine was over the top—it was far more elaborate than the headstone and flowers covering his German grave. You couldn’t stand anywhere in my studio without facing an image of Marcus, but since it was my space, my shrine, my grief, I didn’t give a damn what anyone thought. Besides, almost no one ever came inside.

Burial sites and shrines aside, thanks to my husband’s sense of responsibility, his staunch belief in the importance of insurance, including a very generous travelers’ insurance policy, I was reimbursed for most of the exorbitant bills.

And so, after his body and his emergency medical expenses had been taken care of, after all the checks had been written and the framed photos and candles positioned on my bureau, I had finally arrived at number five on my to-do list: Figure out What to Do with Marcus’s Stuff.

I started with the motorcycle trailer. For as much as I would have liked to have kept the trailer, I couldn’t tow it behind my MINI Cooper. In fact, the trailer was so big my MINI could have fit inside. Marcus had bought the enclosed, wood panel-lined storage-unit-on-wheels for our move from Portland to Mexico, to haul his BMW motorbike. When he bought the immaculate Wells Cargo trailer, I teased him, sayin

g, “This would be the perfect mobile pie shop. We could just cut out a window here,” I said, pointing to the side. “And we could paint ‘The World Needs More Pie’ here,” I added, indicating the blank white area above. “Or I could use it as an extra room, a writing studio. It’s got skylights and air vents. I could really put this to good use.”

He smiled in the deep way that showed his dimples and said, “Hände Weg. Verboten,” the German words for “Keep your hands off. Forbidden.” He had used this expression with me ever since our first Christmas together when he wanted to make certain I didn’t go looking for my present in his suitcase and to tease me, he placed a note, in German, saying as much on top of his luggage. I still have the note, written in his bold, blocky handwriting.

The trailer had journeyed to Mexico and back, packed with Marcus’s motorcycle, our sofa and boxes and boxes of household goods. The roads in Mexico were so bad, so full of potholes and the pavement ultra-slippery when wet, he never did ride the motorcycle there. And after learning of his transfer back to Germany, he had shipped the motorbike directly from Mexico to Stuttgart. The sofa and household goods, however, had all made the return trip to Portland and Marcus’s August vacation was his first chance to unload the trailer. He had spent a full week emptying the trailer and reorganizing our Portland storage unit.

While in the midst of this reorg, he wrote in an email to me in Texas, “Good news. Our storage unit is now packed with the couch, chairs, Chinese medicine cabinet, amazing memory-foam mattress, bar stools, the boxes and all the large tubs. Six small tubs needed to stay in the trailer along with the teak tabletop. Obviously, dealing with this is very ‘un-vacationish.’”

I liked his twist on the English language, and that he even put the made-up word in quotes. I also liked how he noted the detail of the mattress type and called it “amazing.” I had argued for the queen-size version—so we could sleep closer together, as I wanted and needed more intimacy with him—but with our dogs snuggling in bed with us, the king ended up being a good call. In spite of what a pain the thing was to move.

Making Piece

Making Piece